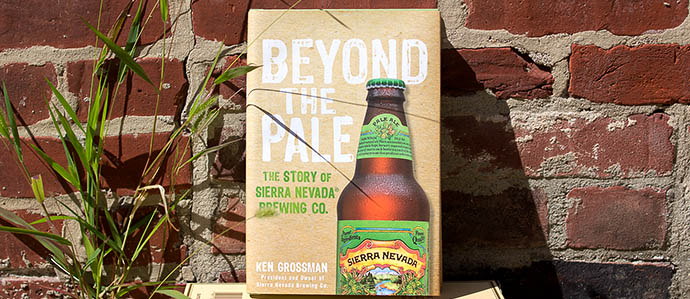

Interview: Sierra Nevada's Ken Grossman on His Book, Hoppy Beers, Farm-to-Tap and More

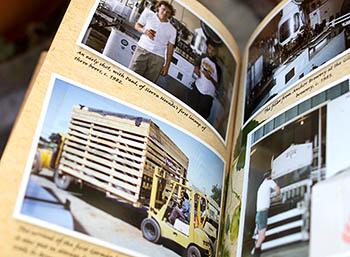

Sierra Nevada’s green-labeled Pale Ale has become a go-to standard in craft beer circles — its ubiquity extends to every bodega, restaurant and bar worth its salt. However, it wasn’t always that way. Beyond the Pale (Wiley, 2013) is a new book by Sierra Nevada founder and CEO Ken Grossman, in which he details his adventures in brewing. After reading the book, we wanted to find out more about the founder and CEO of one of the first and most respected craft breweries in the country, so we rang him up for a quick chat.

The Drink Nation: Between maintaining your current brewery and building a new one, you must be pretty busy. What prompted you to write Beyond the Pale?

Ken Grossman: Actually, I was approached by Sam Calagione from Dogfish Head, who was working on a project about the early days of craft beer. It didn’t come to fruition, but the editors who he had gotten involved asked me if I’d like to tell my own story, since I was one of the first craft breweries in the country and one that sustained all these years. Eventually, I decided that I should.

TDN: When you introduced your Pale Ale, it was one of the hoppiest beers on the market at 30 IBUs. How has Sierra Nevada responded to the hop-monsters coming out of craft breweries, with upwards of 110 IBUs?

TDN: When you introduced your Pale Ale, it was one of the hoppiest beers on the market at 30 IBUs. How has Sierra Nevada responded to the hop-monsters coming out of craft breweries, with upwards of 110 IBUs?

KG: I taste a lot of beers, and I’ve certainly encountered some of the hop-bombs out there. Ultimately, we believe that our pale ale is a benchmark style. We find a lot of customers who enjoy heavily-hopped beers will still come back to our pale ale as their go-to. We do experiment and have done a number of hoppier beers — Hoptimum being one of them, it’s an extreme double IPA. Our Torpedo is somewhat in the middle. We’ve created a wide range of beers to meet customers’ wants and demands, whether for really hoppy beers, or something else.

TDN: Speaking of Torpedo, you pretty much invented the hop torpedo, a “revolutionary dry-hopping device.” Do you consciously try to balance traditional beer styles with innovative processes?

KG: We do embrace traditional brewing roots. We still use whole hops, we still bottle condition most of our beer. So, we haven’t gone away from the brewing traditions that we think make great beer, but we’ve also done a lot with dry hopping and we’ve really pioneered fresh-hop beers. We were the first in the U.S. to do “farm to brew-kettle” beers. We did that 15 years ago. We like to innovate and push boundaries. That said, our heritage is really important to us.

TDN: Some of your innovations are less about beer and more about how you treat your employees — free health clinics, massages, continuing education. Where did these ideas come from?

KG: It comes down to the fundamentals of the company and the culture and what you want in a work environment. Other small breweries do things differently, but we pay attention to treating our employees well. The brewing business has a lot of romance, but in reality it’s a lot of hard work and drudgery and odd shifts. In a brewery, you need to try and mitigate some of the strain by having a fun and happy place to work.

TDN: What do you think are some of the biggest myths or misconceptions of running a brewery?

KG: Well, you run into people and they say “Oh boy, I wish I had your job. I wish I could taste beer all day.” The fact is, there’s the artistic side of brewing — recipe formulation, choosing raw materials, innovating on that front — but there’s also the hard science of brewing: temperature control and oxygen control and trying to reduce the amount of process variables per batch. So you need the art to figure out how to make great beer, but without the science… your beer tastes like buttered popcorn or rotten eggs. You need process clarity to keep the beer the same batch after batch.

TDN: You mentioned the farm-to-brewery process which you use for your Estate series. When did you start that, and how did it come about?

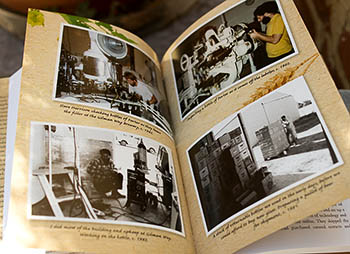

KG: When I had my homebrew shop, I did a bit of malting in my kitchen, so I was aware of turning raw grain into malted grain, and for quite a few years we had wanted to grow some hops here. When I first moved to Chico in 1972, there were hop fields along the highway between Sacramento and Chico, but they disappeared soon thereafter. So we knew hops had been in this area, and we wanted to show people living here today what hops are.

Even a few years ago, many beer drinkers had no idea that hops were a flower, or what malt was at all. We were kind of putting on a show-and-tell to brewery visitors when we planted our hop field 10 years ago. We had one of the first hop fields in a brewery in the country! And then we started making beer from those hops — I bought a hop-picking machine from Germany. That led us to think, “Well, let’s make our own barley and malt as well,” so we started growing barley about five or six years ago, and now the Estate Ale is made with our own barley and our own hops.

TDN: Very cool. On that subject, what’s the story behind the DevESTATEtion Ale you made this year?

TDN: Very cool. On that subject, what’s the story behind the DevESTATEtion Ale you made this year?

KG: Well, when you grow your own ingredients, sometimes you have to contend with Mother Nature, and she can be kind or cruel. This year we had a series of weather events that led to barley that was too high in protein to make good beer. Not that we couldn’t have made beer from it, but when we harvested it and sent it to the lab, it turned out the protein was significantly higher than we would like to see (it was at 15% and we like to keep it between 10-12%). So we had to make the decision of whether to go through the trouble of having the barley malted,knowing that it wasn’t ideal to make beer. We decided not take that gamble, and made DevESTATEtion instead.

TDN: What are some of the most exciting things that you’re seeing in the craft beer community now?

KG: The dynamic of the craft beer world is creating a very rapid succession of styles. The range of beer that’s available from craft brewers in the U.S. today is wider than anywhere else in the world, by far. Stylistically, the brewers are really pushing limits and boundaries and reinterpreting styles of beers that were brewed hundreds and thousands of years ago. I don’t know if there’s any one specific thing, but from Allagash doing cool brewing to Russian River doing lots of interesting things with wild yeast, there’s a lot of exciting stuff out there, and the quantity of it is impressive. It’s a pretty exciting time to be a brewer, and a consumer.

TDN: You got started during a boom in homebrewing and craft beer making in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Do you feel there’s been a revival of interest in the past decade?

KG: Most definitely. It’s a bit different now than it was then, because now the consumers are really educated, and they are the ones driving the excitement and awareness. Back when we were first starting, the knowledge about beer and brewing wasn’t there. Today with the internet and blogs, the industry is a completely different ballgame than even 15 years ago.

TDN: Sierra Nevada is building a new brewery in North Carolina. What prompted that?

KG: Shipping beer from northern California to the East Coast was causing some energy and carbon footprint concerns. We knew that at some point, if we were to continue to have growth on the East Coast, we’d need to address that from an environmental and sensibility standpoint. We made the decision several years ago to look for an eastern location, and we chose the Asheville, North Carolina location.

TDN: Do you have any advice for people looking to get into the industry?

KG: When I started there wasn’t anything like the Craft Brewers Associations or the magazines and books that are available, but today there’s a huge amount of information available from both a brewing standpoint and from a small-business standpoint. The avenues are wide open for new brewers right now.

Photos by Danya Henninger