Repeal Day: A Brief History of Prohibition and Its Demise

Each year on December 5, drinkers around the United States commemorate Repeal Day. It was on this date in 1933 that Utah became the 33rd state to ratify the 21st Amendment, thereby repealing the 18th Amendment and ending the disastrous experiment known as Prohibition. Alcohol sales became legal again, and the rest is history.

A Drinking Problem

Why did Prohibition come about in the first place? In the America of the 1800s, alcohol abuse was rampant. In 1820, the average American consumed 90 bottles of 80-proof liquor per year. That’s a bottle every four days, for every man and woman in the newly formed country.

Why did Prohibition come about in the first place? In the America of the 1800s, alcohol abuse was rampant. In 1820, the average American consumed 90 bottles of 80-proof liquor per year. That’s a bottle every four days, for every man and woman in the newly formed country.

Whiskey and rye were early favorites, and could be had for cheap at any time of day, in nearly any establishment that sold comestibles. With the influx of German and Irish immigrants in the 1840s and ‘50s, beer started to become more popular, and brewers even took to recommending mothers feed sips of it to their newborn babies.

The Temperance Movement

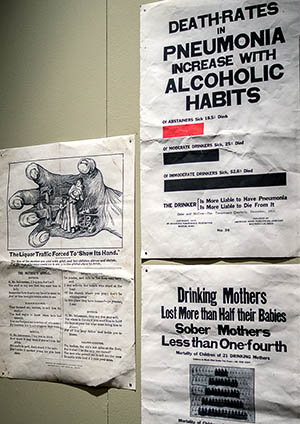

The most well-known temperance advocate of the early 1900s was Carrie Nation, who was a woman of large stature who famously took hachets into saloons and laid waste to the entire contents of the bar. Women in general started the movement to curtail alcohol sales, and they were joined by evangelical churches in their quest to clean up America. Propaganda-style posters were printed up, with frightening statistics about how alcohol abuse led to birth defects and younger deaths.

The most well-known temperance advocate of the early 1900s was Carrie Nation, who was a woman of large stature who famously took hachets into saloons and laid waste to the entire contents of the bar. Women in general started the movement to curtail alcohol sales, and they were joined by evangelical churches in their quest to clean up America. Propaganda-style posters were printed up, with frightening statistics about how alcohol abuse led to birth defects and younger deaths.

The campaign grew into a political movement. During World War I, the Prohibition Party and the Anti-Saloon League drew on anti-German sentiment to suggest that beer was a way the enemy was causing the downfall of America. Women’s groups connected the quest for temperance with a push for suffrage, the right to vote. On January 16, 1919 — thanks to many behind-the-scenes political machinations — the18th Amendment was passed.

Outside the Law

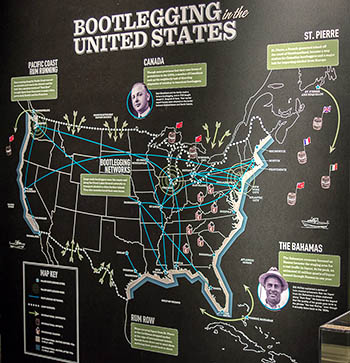

Thanks to the rules enumerated in the Volstead Act, what by some measures was the nation’s fifth-largest industry was shut down nearly overnight. Americans did start drinking less, but alcohol did not disappear — people simply turned to illegal methods of making, shipping and selling alcohol. Loopholes in enforcement laws meant the mafia and other underground organizations benefited, and became rich selling untaxed booze throughout the country.

Where were they getting the liquor to sell? There were also loopholes in the Volstead Act that allowed production. For example, households could “preserve fruit” through fermentation, ostensibly for family use. Religious wine was allowed. And doctors were allowed to prescribe “medicinal alcohol.” Criminals obtained this booze or made their own, and sold it for huge profits. Al Capone ran the liquor trade from Canada to Florida, and controlled Chicago and other cities. Police were either crooked or helpless. Speakeasies flourished everywhere.

Where were they getting the liquor to sell? There were also loopholes in the Volstead Act that allowed production. For example, households could “preserve fruit” through fermentation, ostensibly for family use. Religious wine was allowed. And doctors were allowed to prescribe “medicinal alcohol.” Criminals obtained this booze or made their own, and sold it for huge profits. Al Capone ran the liquor trade from Canada to Florida, and controlled Chicago and other cities. Police were either crooked or helpless. Speakeasies flourished everywhere.

Tax the Drinks

Then the Great Depression came. Unemployment rose and the coffers of the United States government, dependent on taxes, were dangerously low. Desperate for funds, elected officials and politicians began to consider repeal of the 18th Amendment as a possible solution — legal alcohol meant a huge boost in tax revenue. Even though the repeal of a constitutional amendment had never been accomplished in U.S. history, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt came out for repeal in his 1932 presidential campaign, the chances of success began to look possible.

FDR was elected, of course, and in March of 1933 he signed into law the Cullen-Harrison Act, allowing sales of alcohol up to 3.2% (very low ABV beer falls into this category). Congress drafted and passed the 21st Amendment, and it was eventually ratified — though by the previously unused (and never again used) method of state conventions, rather than state legislatures. This was because the temperance movement was still quite active in several statehouses.

State by State

The 21st Amendment gave state governments two options: a state could choose to directly control the entire alcohol industry or to regulate via licenses to private enterprise. Even today, some states are “control states,” and keep a monopoly on wholesaling and/or retailing beer, wine and/or liquor.

For example, in Pennsylvania, only the state can sell wine and spirits, and beer sales are not permitted in grocery stores. Mississippi enacted statewide general prohibition in 1908, and didn’t end it until 1966. In Kentucky — that bastion of bourbon production — 39 of 120 counties are completely dry, to this day.

Acknowledgement

Many images and information in this article are thanks to the National Constitution Center’s exhibit “American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.”

Photos by Danya Henninger

Tags: Education, Spirits